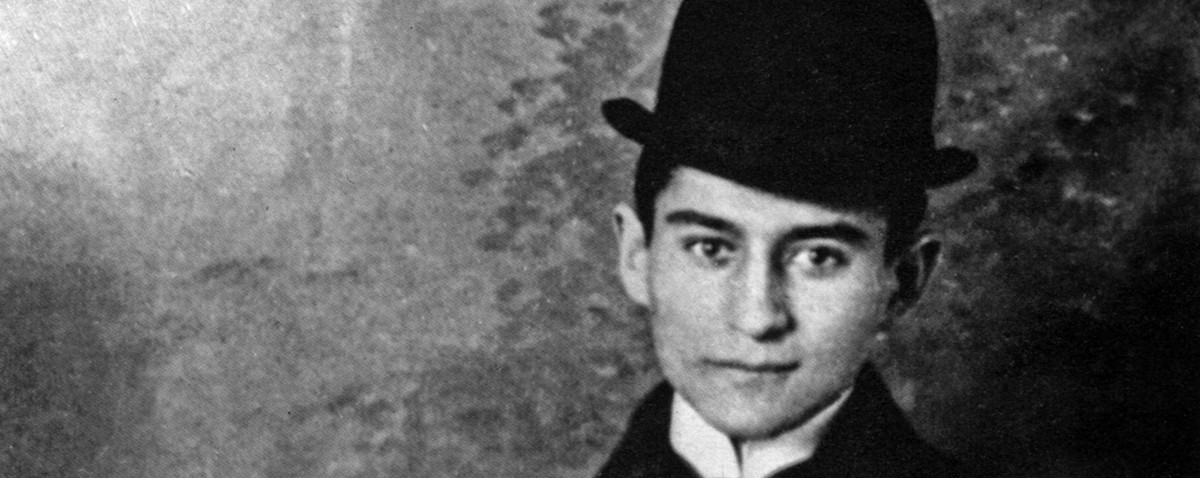

My recent post about Thomas Wolfe elicited a handful of comments like, “I loved to read him when I was young, but as I get older he no longer holds up.” My own versions of Wolfe are people like Hesse and Dostoevsky, but Kafka has remained one of those authors I latched onto in high school who has never lost his power. It’s still a vivid memory, working my first summer job and hiding out, reading Stanley Corngold’s edition of The Metamorphosis, which included a section of notes as long as the story itself. Almost immediately, then, I was introduced to something beyond literary criticism or interpretation, and closer to midrash.

My recent post about Thomas Wolfe elicited a handful of comments like, “I loved to read him when I was young, but as I get older he no longer holds up.” My own versions of Wolfe are people like Hesse and Dostoevsky, but Kafka has remained one of those authors I latched onto in high school who has never lost his power. It’s still a vivid memory, working my first summer job and hiding out, reading Stanley Corngold’s edition of The Metamorphosis, which included a section of notes as long as the story itself. Almost immediately, then, I was introduced to something beyond literary criticism or interpretation, and closer to midrash.

And as I started with Corngold’s introduction, the first words of Kafka I actually read were the entries excerpted there from his diaries, among them: “What will be my fate as a writer is very simple. My talent for portraying my dreamlike inner life has thrust all other matters into the background; my life has dwindled dreadfully, nor will it cease to dwindle. Nothing else will ever satisfy me.” Such ideas poured into the mind of a teenager who already felt isolated were beyond potent, and for better or worse they have never lost their influence. (This to say nothing of the content of The Metamorphosis itself, a veritable blueprint of alienation and misunderstanding, of familial and social humiliation, of familial and social brutality.)

This past summer I finally got around to reading the entirety of his diaries, and below are just the highlights of Kafka trying to write, not being able to write, finally writing, dealing with his parents and family and career in insurance, agonizing over love and the possibility of marriage and family, and feeling beyond empty when none of these things work out. Perhaps his editor and friend, Max Brod, was correct in the afterword, warning that diaries are usually collections of negativity and grumblings, and that Kafka’s are even more so; but even if Kafka wasn’t as obsessive or depressed as his diaries suggest, his words still ring true for the millions of anonymous writers out there.

***

I write this very decidedly out of despair over my body and over a future with this body. 10

Finally, after five months of my life during which I could write nothing that would have satisfied me, and for which no power will compensate me, though all were under obligation to do so, it occurs to me to talk to myself again. Whenever I really questioned myself, there was always a response forthcoming, there was always something in me to catch fire, in this heap of straw that I have been for five months and whose fate, it seems, is to be set afire during the summer and consumed more swiftly than the onlooker can blink his eyes. If only that would happen to me! And tenfold ought that to happen to me, for I do not even regret this unhappy time. 12

Sunday, 19 July, slept, awoke, slept, awoke, miserable life. 14

I will not left myself become tired. I’ll jump into my story even though it should cut my face to pieces. 28

I won’t give up the diary again. I must hold on here, it is the only place I can. 29

The pursuit of the secondary characters I read about in novels, plays, etc. This sense of belonging together which I then have! In the Jungfern von Bischofsberg (is that the title?), there is mention made of two seamstresses who sew and linen for the play’s one bride. What happens to these two girls? Where do they live? What have they done that they may not be part of the play but stand, as it were, outside in front of Noah’s ark, drowning in the downpour of rain, and may only press their faces one last time against a cabin window, so that the audience in the stalls sees something dark there for a moment? 30

That I have put aside and crossed out so much, indeed almost everything I wrote this year, that hinders me a great deal in writing. It is indeed a mountain, it is five times as much as I have in general ever written, and by its mass alone it draws everything that I write away from under my pen to itself. 30

That I, so long as I am not freed of my office, am simply lost, that is clearer to me than anything else, it is just a matter, as long as it is possible, of holding my head so high that I do not drown. How difficult that will be, what strength it will necessarily drain me of, can be seen already in the fact that today I did not adhere to my new time schedule, to be at my desk from 8 to 11pm, that at present I even consider this as not so very great a disaster, that I have only hastily written down these few lines in order to get into bed. 31

How do I excuse my not yet having written anything today? 31

Wretched, wretched, and yet with good intentions. It is midnight, but since I have slept very well, that is an excuse only to the extent that by day I would have written nothing. The burning electric light, the silent house, the darkness outside, the last waking moments, they give me the right to write even if it be only the most miserable stuff. And this right I use hurriedly. That’s the person I am. 33

I cannot now devote myself completely to this literary field, as would be necessary and indeed for various reasons. Aside from my relationships, I could not live by literature if only, to begin with, because of the slow maturing of my work and its special character; besides, I am prevented also by my health and my character from devoting myself to what is, in the most favorable case, an uncertain life. I have therefore become an official in a social insurance agency. Now these two professions can never be reconciled with one another and admit a common fortune. The smallest good fortune in one becomes a great misfortune in the other. If I have written something good one evening, I am afire the next day in the office and can bring nothing to completion. This back and forth continually becomes worse. Outwardly, I fulfill my duties satisfactorily in the office, not my inner duties, however, and every unfulfilled inner duty becomes a misfortune that never leaves. 49

One should laugh in the office because there is nothing better to be accomplished there. 53

I believe this sleeplessness comes only because I write. For no matter how little and how badly I write, I am still made sensitive by these minor shocks, feel, especially towards evening and even more in the morning, the approaching, the imminent possibility of great moments which would tear me open, which could make me capable of anything, and in the general uproar that is within me and which I have no time to command, find no rest. In the end this uproar is only a suppressed, restrained harmony, which, left free, would fill me completely, which could even widen me and yet still fill me. But now such a moment arouses only feeble hopes and does me harm, for my being does not have sufficient strength of the capacity to hold the present mixture, during the day the visible word helps me, during the night it cuts me to pieces unhindered. 61

If I reach my fortieth year, then I’ll probably marry an old maid with protruding upper teeth left a little exposed by the upper lip. The upper front teeth of Miss K., who was in Paris and London, slant towards each other a little like legs which are quickly crossed at the knees. I’ll hardly reach my fortieth birthday, however; the frequent tension over the left half of my skull, for example, speaks against it—it feels like an inner leprosy which, when I only observe it and disregard its unpleasantness, makes the same impression on me as the skull cross-section in textbooks, or as an almost painless dissection of the living body where the knife—a little coolingly, carefully, often stopping and going back, sometimes lying still—splits still thinner the paper-thin integument close to the functioning parts of the brain. 70-1

In the end this is little consolation for me. The free years he spent in London are already past for me, the possible happiness becomes ever more impossible, I lead a horrible synthetic life and am cowardly and miserable enough to follow Shaw only to the extent of having read the passage to my parents. How this possible life flashes before my eyes in colors of steel, with spanning rods of steel and airy darkness between! 91

This craving that I almost always have, when for once I feel my stomach is healthy, to heap up in me notions of terrible deeds of daring wit food. I especially satisfy this craving in front of pork butchers. If I see a sausage that is labelled as an old, hard sausage, I bite into it in my imagination with all my teeth and swallow quickly, regularly, and thoughtlessly, like a machine. The despair that this act, even in the imagination, has as its immediate result, increase my haste. I shove the long slabs of rib meat unbitten into my mouth, and then pull them out again from behind, tearing through stomach and intestines. I eat dirty delicatessen stores completely empty. Cram myself with herrings, pickles, and all the bad, old, sharp food. Bonbons are poured into me like hail from their tin boxes. I enjoy in this way not only my healthy condition but also a suffering that is without pain and can pass at once. 96

This afternoon the pain occasioned by my loneliness came upon me so piercingly and intensely that I became aware that the strength which I gain through this writing thus spends itself, a strength which I certainly have not intended for this purpose. 101

This morning, for the first time in a long time, the joy again of imagining a knife twisted in my heart. 101

When the lawyer, in reading the agreement [about the shares in the factory] to me, came to a passage concerning my possible future wife and possible children, I saw across from me a table with two large chairs and a smaller one around it. At the thought that I should never be in a position to seat in these or any other three chairs myself, my wife, and my child, there came over me a yearning for this happiness so despairing from the very start that in my excitement I asked the lawyer the only question I had left after the long reading, which at once revealed my complete misunderstanding of a rather long section of the agreement that had just been read. 110

It seems so dreadful to be a bachelor, to become an old man struggling to keep one’s dignity while begging for an invitation whenever one wants to spend an evening in company, having to carry one’s meal home in one’s hand, unable to expect anyone with a lazy sense of calm confidence, able only with difficulty and vexation to give a gift to someone, having to say good night at the front door, never being able to run up a stairway beside one’s wife, to lie ill and have only the solace of the view from one’s window when one can sit up, to have only side doors in one’s room leading into other people’s living rooms, to feel estranged from one’s family, with whom one can keep on close terms only by marriage, first by the marriage of one’s parents, then, when the effect of that has worn off, by one’s own, having to admire other people’s children and not even being allowed to go on saying: “I have none myself,” never to feel oneself grow older since there is no family growing up around one, modeling oneself in appearance and behavior on one or two bachelors remembered from our youth.

This is all true, but it is easy to make the error of unfolding future sufferings so far in front of one that one’s eye must pass beyond them and never again return, while in reality, both today and later, one will stand with a palpable body and a real head, a real forehead that is, for smiting on one’s hand. 117

In the past I could not express myself freely in the company of new acquaintances because the presence of sexual wishes unconsciously hindered me, now their conscious absence hinders me. 133

When I began to write after a rather long interval, I draw the words as if out of the empty air. If I capture one, then I have just this one alone and all the toil must begin anew. 137

The moment I were set free from the office I would yield at once to my desire to write an autobiography. 140

I hate Werfel, not because I envy him, but I envy him too. He is healthy, young and rich, everything that I am not. Besides, gifted with a sense of music, he has done very good work early and easily, he had the happiest life behind him and before him, I work with weights I cannot get rid of, and am entirely shut off from music. 141

Today at breakfast I spoke with my mother by chance about children and marriage, only a few words, but for the first time saw clearly untrue and childish is the conception of me that my mother builds up for herself. She considers me a healthy young man who suffers a little from the notion that he is ill. This notion will disappear by itself with time; marriage, of course, and having children would put an end to it best of all. Then my interest in literature would also be reduced to the degree that is perhaps necessary for an educated man. A matter-of-fact, undisturbed interest in my profession or in the factory or in whatever may come to hand will appear. Hence there is not the slightest, not the trace of a reason for permanent despair, which is not very deep, however, whenever I think my stomach is upset, or when I can’t sleep because I write too much. There are thousands of possible solutions. The most probable is that I shall suddenly fall in love with a girl and will never again want to do without her. Then I shall see how good their intentions towards me are and how little they will interfere with me. But if I remain a bachelor like my uncle in Madrid, that too will be no misfortune because with my cleverness I shall know how to make adjustments. 143

One advantage in keeping a diary is that you become aware with reassuring clarity of the changes which you constantly suffer and which in a general way are naturally believed, surmised, and admitted by you, but which you’ll unconsciously deny when it comes to the point of gaining hope or peace from such an admission. In the diary you find proof that in situations which today would seem unbearable, you lived, looked around and wrote down observations, that this right hand moved then as it does today, when we may be wiser because we are able to look back upon our former condition, and for that very reason have got to admit the courage of our earlier striving in which we persisted even in sheer ignorance. 145

Goethe probably retards the development of the German language by the force of his writing. 152

It is easy to recognize a concentration in me of all my forces on writing. When it became clear in my organism that writing was the most productive direction for my being to take, everything rushed in that direction and left empty all those abilities which were directed towards the joys of sex, eating, drinking, philosophical reflection, and above all music. I atrophied in all these directions. This was necessary because the totality of my strengths was so slight that only collectively could they even half-way serve the purpose of my writing. Naturally, I did not find this purpose independently and consciously, it found itself, and is now interfered with only by the office, but that interferes with it completely. In any case I shouldn’t complain that I can’t put up with a sweetheart, that I understand almost exactly as much of love as I do of music and have to resign myself to the most superficial efforts I may pick up, that on New Year’s Eve I dined on parsnips and spinach, washed down with a glass of Ceres, and that on Sunday I was unable to take part in Max’s lecture on his philosophical work—the compensation for all this is clear as day. My development is now complete and, so far as I can see, there is nothing left to sacrifice; I need only throw my work in the office out of this complex in order to begin my real life in which, with the progress of my work, my face will finally be able to age in a natural way. 163

For two days I have noticed, whenever I choose to, an inner coolness and indifference. Yesterday evening, during my walk, every little street sound, every eye turned towards me, every picture in a showcase, was more important to me than myself. 165

My impatience and grief because of my exhaustion are nourished especially on the prospect of the future that is thus prepared for me and which is never out of my sight. What evenings, walks, despair in bed and on the sofa are still before me, worse than those I have already endured! 179

A new stabilizing force has recently appeared in my deliberations about myself which I can recognize now for the first time and only now, since during the last week I have been literally disintegrating because of sadness and uselessness. 182

Read through some old notebooks. It takes all my strength to last it out. The unhappiness one must suffer when one interrupts oneself in a task that can never succeed except all at once, and this is what has always happened to me until now; in rereading one must re-experience this unhappiness in a more concentrated way though not as strongly as before.

Today, while bathing, I thought I felt old powers, as though they had been untouched by the long interval. 192

So deserted by myself, by everything. Noise in the next room. 193

Today burned many old, disgusting papers. 193

16 March. Saturday. Again encouragement. Again I catch hold of myself, as one catches hold of a ball in its fall. Tomorrow, today, I’ll begin an extensive work which, without being forced, will shape itself according to my abilities. I will not give it up as long as I can hold out at all. rather be sleepless that live on in this way. 196

Without weight, without bones, without body, walked through the streets for two hours considering what I overcame this afternoon while writing. 204

Nothing written for so long. Begin tomorrow. Otherwise I shall again get into a prolonged, irresistible dissatisfaction; I am really in it already. The nervous states are beginning. But if I can do something, then I can do it without superstitious precaution. 204

Nothing, nothing. How much time the publishing of the little book takes from me and how much harmful, ridiculous pride comes from reading old things with an eye to publication. Only that keeps me from writing. And yet in reality I have achieved nothing, the disturbance is the best proof of it. 205

The hollow which the work of genius has burned into our surroundings is a good place into which to put one’s little light. Therefore the inspiration that emanates from genius, the universal inspiration that doesn’t only drive one to imitation. 210

23 September [1912]. This story, “The Judgment,” I wrote at one sitting during the night of the 22nd-23rd, from ten o’clock at night to six o’clock in the morning. I was hardly able to pull my legs out from under the desk, they had got so stiff from sitting. The fearful strain and joy, how the story developed before me, as if I were advancing over water. Several times during this night I heaved my own weight on my back. How everything can be said, how for everything, for the strangest fancies, there waits a great fire in which they perish and rise up again. How it turned blue outside the window. A wagon rolled by. Two men walked across the bridge. At two I looked at the clock for the last time. As the maid walked through the anteroom for the first time I wrote the last sentence. Turning out the light and the light of day. The slight pains around my heart. The weariness that disappeared in the middle of the night. The trembling entrance into my sisters’ room. Reading aloud. Before that, stretching in the presence of the maid and saying, “I’ve been writing until now.” The appearance of the undisturbed bed, as though it had just been brought in. The conviction verified that with my novel-writing I am in the shameful lowlands of writing. Only in this way can writing be done, only with such coherence, with such a complete opening out of the body and the soul. Morning in bed. The always clear eyes. Many emotions carried along in the writing, joy, for example, that I shall have something beautiful for Max’s Arkadia, thoughts about Freud, of course; in one passage, of Arnold Beer; in another, of Wassmermann; in one, of Werfel’s giantess; of course, also of my “The Urban World.” 212-3

It has become very necessary to keep a diary again. The uncertainty about my thoughts., F., the ruin in the office, the physical impossibility of writing and the inner need to do it. 219

The terrible uncertainty of my inner existence. 220

The tremendous world I have in my head. But how [to] free myself and free it without being torn to pieces. And a thousand times rather be torn to pieces than retain it in my or bury it. That, indeed, is why I am here, that is quite clear to me. 222

When I say something it immediately and finally loses its importance, when I write it down it loses it too, but sometimes gains a new one. 223

Don’t despair, not even over the fact that you don’t despair. Just when everything seems over with, new forces come marching up, and precisely that means that you are alive. 224

To be pulled in through the ground-floor window of a house by a rope tied around one’s neck and to be yanked up, bloody and ragged, through all the ceilings, furniture, walls, and attics, without consideration, as if by a person who is paying no attention, until the empty noose, dropping the last fragments of me when it breaks through the roof tiles, is seen on the roof. 224

Summary of all the arguments for and against my marriage:

- Inability to endure life alone, which does not imply inability to live, quite the contrary, it is even improbable that I know how to live with anyone, but I am incapable, alone, of bearing the assault of my own life, the demands of my own person, the attacks of time and old age, the vague pressure of the desire to write, sleeplessness, the nearness of insanity—I cannot bear all this alone. I naturally add a “perhaps” to this. The connection with F. will give my existence more strength to resist.

- Everything immediately gives me pause. Every joke in the comic paper, what I remember about Flaubert and Grillparzer, the sight of the nightshirts on my parents’ beds, laid out for the night, Max’s marriage. Yesterday my sister said, “All the married people (that we know) are happy, I don’t understand it,” this remark too gave me pause, I became afraid again.

- I must be alone a great deal. What I accomplished was only the result of being alone.

- I hate everything that does not relate to literature, conversations bore me (even if they relate to literature), to visit people bores me, the sorrows and joys of my relatives bore me to my soul. Conversations take the importance, the seriousness, the truth of everything I think.

- The fear of the connection, of passing into the other. Then I’ll never be alone again.

- In the past, especially, the person I am in the company of my sisters has been entirely different from the person I am in the company of other people. Fearless, powerful, surprising, moved as I otherwise am only when I write. If through the intermediation of my wife I could be like that in the presence of everyone! But then would it not be at the expense of my writing? Not that, not that!

- Alone, I could perhaps some day really give up my job. Married, it will never be possible. 225

Nothing, nothing, nothing. Weakness, self-destruction, tip of a flame of hell piercing the floor. 227

Perhaps everything is now ended and the letter I wrote yesterday was the last one. That would certainly be the best. What I shall suffer, what she will suffer—that cannot be compared with the common suffering that would result. I shall gradually pull myself together, she will marry, that is the only way out among the living. We cannot beat a path into the rock for the two of us, it is enough that we wept and tortured ourselves for a year. She will realize this from my last letters. If not, then I will certainly marry her, for I am too weak to resist her opinion about our common fortune and am unable not to carry out, as far as I can, something she considers possible. 227-228

Coitus as punishment for the happiness of being together. Live as ascetically as possible, more ascetically than a bachelor, that is the only possible way for me to endure marriage. But she?

And despite all this, if we, I and F., had equal rights, if we had the same prospects and possibilities, I would not marry. But this blind alley into which I have slowly pushed her life makes it an unavoidable duty for me, although its consequences are by no means unpredictable. Some secret law of human relationship is at work here.

I had great difficulty writing the letter to her parents, especially because a first draft, written under particularly unfavorable circumstances, for a long time resisted every change. Today, nevertheless, I have just about succeeded, at least there is no untruth in it, and after all it is still something that parents can read and understand. 228

Agonies in bed towards morning. Saw only solution in jumping out of the window. My mother came to my bedside and asked whether I had sent off the letter and whether it was my original text. I said it was the original text, but made even sharper. She said she does not understand me. I answered, she most certainly does not understand me, and by no means only in this matter. 228

Today I got Kierkegaard’s Buch des Richters. As I suspected, his case, despite essential differences, is very similar to mine, at least he is on the same side of the world. He bears me out like a friend. 230

My job is unbearable to me because it conflicts with my only desire and my only calling, which is literature. Since I am nothing but literature and can and want to be nothing else, my job will never take possession of me, it may, however, shatter me completely, and this is by no means a remote possibility. Nervous states of the worst sort control me without pause, and this year of worry and torment about my and your daughter’s future has revealed to the full my inability to resist. You might ask why I do not give up this job and—I have no money—do not try to support myself by literary work. To this I can make only the miserable reply that I don’t have the strength for it, and that, as far as I can see, I shall instead be destroyed by this job, and destroyed quickly. 230

Conclusions can at least be drawn from the sort of life I lead at home. Well, I live in my family, among the best and most lovable people, more strange than a stranger. I have not spoken an average of twenty words a day to my mother these last years, hardly ever said more than hello to my father. I do not speak at all to my married sisters and my brothers-in-law, and not because I have anything against them. The reason for it is simply this, that I have not the slightest thing to talk to them about. Everything that is not literature bores me and I hate it, for it disturbs me or delays me, if only because I think it does. I lack all aptitude for family life except, at best, as an observer. I have no family feeling and visitors make me almost feel as though I were maliciously being attacked. A marriage could not change me, just as my job cannot change me. 231

I don’t even have the desire to keep a diary, perhaps because there is already too much lacking in it, perhaps because I should perpetually have to describe incomplete—by all appearances necessarily incomplete—actions, perhaps because writing itself adds to my sadness. 233

All things resist being written down. 234

I will write again, but how many doubts have I meanwhile had about my writing? At bottom I am an incapable, ignorant person who, if he had not been compelled—without any effort on his own part and scarcely aware of the compulsion—to go to school, would be fit only to crouch in a kennel, to leap out when food is offered him, and to leap back when he has swallowed it. 237

View from the outside it is terrible for a young but mature person to die, or worse, to kill himself. Hopelessly to depart in a completely confusion that would make sense only within a further development, or with the sole hope that in the great account this appearance in life will be considered as not having taken place. Such would be my plight now. To die would mean nothing else than to surrender a nothing to the nothing, but that would be impossible to conceive, for how could a person, even only as a nothing, consciously surrender himself to the nothing, and not merely to an empty nothing but rather to a roaring nothing whose nothingness consists only in its incomprehensibility. 243

Wonderful, entirely self-contradictory idea that someone who died at 3 a.m., for instance, immediately thereafter, about dawn, enters into a higher life. What incompatibility there is between the visibly human and everything else! How out of one mystery there always comes a greater one! In the first moment the breath leaves the human calculator. Really one should be afraid to step out of one’s house. 244

Uncertainty, aridity, peace—all things will resolved themselves into these and pass away. 252

What have I in common with Jews? I have hardly anything in common with myself and should stand very quietly in a corner, content that I can breathe. 252

Anxiety alternating with self-assurance at the office. Otherwise more confident. Great antipathy to “Metamorphosis.” Unreadable ending. Imperfect almost to its very marrow. It would have turned out much better if I had not been interrupted at the time by the business trip. 253

There will certainly be no one to blame if I should kill myself, even if the immediate cause should for instance appear to be F.’s behavior. Once, half asleep, I pictured the scene that would ensue if, in anticipation of the end, the letter of farewell in my pocket, I should come to her house, should be rejected as a suitor, lay the letter on the table, go to the balcony, break away from all those who run up to hold me back, and, forcing one hand after another to let go its grip, jump over the ledge. The letter, however, would say that I was jumping off because of F., but that even if my proposal had been accepted nothing essential would have been changed for me. My place is down below, I can find no other solution, F. simply happens to be the one through whom my fate is made manifest; I can’t live without her and must jump, yet—and this F. suspects—I couldn’t live with her either. Why not use tonight for the purpose, I can already see before me the people talking at the parents’ gathering this evening, talking of life and the conditions that have to be created for it-but I cling to abstractions, I live completely entangled in life, I won’t do it, I am cold, am sad that a shirt collar is pinching my neck, am damned, gasp for breath in the mist. 259

I too am losing Felix by this marriage. A friend who is married is none. 260

Moreover, as a result of my dependence, which is at least encouraged by this way of life, I approach everything hesitantly and complete nothing at the first stroke. That was what happened here too. 262

If only it were possible to go to Berlin, to become independent, to live from one day to the next, even to go hungry, but to let all one’s strength pour forth instead of husbanding it here, or rather—instead of one’s turning aside into nothingness! If only F. wanted it, would help me! 267

Tomorrow to Berlin. Is it a nervous or a real, trustworthy security that I feel? How is that possible? Is it true that if one once acquires a confidence in one’s ability to write, nothing can miscarry, nothing is wholly lost, while at the same time only seldom will something rise up to a more than ordinary height? It this because of my approaching marriage to F.? Strange condition, though not entirely unknown to me when I think back. 274

“Don’t you want to join us?” I was recently asked by an acquaintance when he ran across me alone after midnight in a coffee-house that was already almost deserted. “No, I don’t,” I said. 277

To have to bear and to be the cause of such suffering! 293

Evening alone on a bench on Unter den Linden. Stomach-ache. Sad-looking ticket-seller. Stood in front of people, shuffled the tickets in his hands, and you could only get rid of him by buying one. Did his job properly in spite of all his apparent clumsiness—on a full-time job of this kind you can’t keep jumping around; he must also try to remember people’s faces. When I see people of this kind I always think: How did he get into this job, how much does he make, where will he be tomorrow, what awaits him in his old age, where does he live, in what corner does he stretch out his arms before going to sleep, could I do his job, how should I feel about it? All this together with my stomach-ache. Suffered through a horrible night. And yet almost no recollection of it. 293

I shun people not because I want to live quietly, but rather because I want to die quietly. 295

But I will write in spite of everything, absolutely; it is my struggle for self-preservation. 300

2 August [1914]. Germany has declared war on Russia – Swimming in the afternoon. 301

What will be my fate as a writer is very simple. My talent for portraying my dreamlike inner life has thrust all other matters into the background; my life has dwindled dreadfully, nor will it cease to dwindle. Nothing else will ever satisfy me. But the strength I can muster for that portrayal is not to be counted upon: perhaps it has already vanished forever, perhaps it will come back to me again, although the circumstances of my life don’t favor its return. Thus I waver, continually fly to the summit of the mountain, but then fall back in a moment. Others waver too, but in lower regions, with greater strength; if they are in danger of falling, they are caught up by the kinsman who walks beside them for that very purpose. But I waver on the heights; it is not death, alas, but the enteral torments of dying. 302

I have been writing these past few days, may it continue. Today I am not so completely protected by and enclosed in my work as I was two years ago, nevertheless have the feeling that my monotonous, empty, mad bachelor’s life has some justification. I can once more carry on a conversation with myself, and don’t stare so into complete emptiness. Only I this way is there any possibility of improvement for me. 303

21 August. In this ridiculous hope, which apparently has only some mechanical notion behind it of how things work, I start The Trial again—The effort wasn’t entirely without result.

29 August. The end of one chapter a failure; another chapter, which began beautifully, I shall hardly—or rather certainly not—be able to continue as beautifully, while at the time, during the night, I should certainly have succeeded with it. But I must not forsake myself, I am entirely alone.

30 August. Cold and empty. I feel only too strongly the limits of my abilities, narrow limits, doubtless, unless I am completely inspired. And I believe that even in the grip of inspiration I am swept along only within these narrow limits, which, however, I then no longer feel because I am being swept along. Nevertheless, within these limits there is room to live, and for this reason I shall probably exploit them to a despicable degree. 313

Leafed through the diary a little. Got a kind of inkling of the way a life like this is constituted. 316

I can’t write any more. I’ve come up against the last boundary, before which I shall in all likelihood again sit down for years, and then in all likelihood begin another story all over again that will again remain unfinished. This fate pursues me. And I have become cold again, and insensible; nothing is left but a senile love for unbroken calm. And like some kind of beast at the farthest pole from man, I shift my neck from side to side again and for the time being should like to try to have F. back. I’ll really try it, if the nausea I feel for myself doesn’t prevent me. 318

On the way home told Max that I shall lie very contentedly on my deathbed, provided the pain isn’t too great. I forgot—and later purposely omitted—to add that the best things I have written have their basis in this capacity of mine to meet death with contentment. All these fine and very convincing passages always deal with the fact that someone is dying, that it is hard for him to do, that it seems unjust to him, or at least harsh, and the reader is moved by this, or at least he should be. But for me, who believe that I shall be able to lie contentedly on my deathbed, such scenes are secretly a game; indeed, in the death enacted I rejoice in my own death, hence calculatingly exploit the attention that the reader concentrates on death, have a much clearer understanding of it than he, of whom I suppose that he will loudly lament on his deathbed, and for these reasons my lament is as perfect as can be, nor does it suddenly break off, as is likely to be the case with a real lament, but dies beautifully and purely away. It is the same thing as my perpetual lamenting to my mother over pains that were not nearly so great as my laments would lead one to believe. With my mother, of course, I did not need to make so great a display of art as with the reader. 321

The beginning of every story is ridiculous at first. There seems no hope that this newborn thing, still incomplete and tender in every joint, will be able to keep alive in the completed organization of the world, which, like every completed organization, strives to close itself off. However, one should not forget that the story, if it has any justification to exist, bears its complete organization within itself even before it has been fully formed; for this reason despair over the beginning of a story is unwarranted; in a like case parents should have to despair of their suckling infant, for they had no intention of bringing this pathetic and ridiculous being into the world. Of course, one never knows whether the despair one feels is warranted or unwarranted. But reflecting on it can give one a certain support; in the past I have suffered from the lack of this knowledge. 322

I shall not be able to write so long as I have to go to the factory. I think it is a special inability to work that I feel now, similar to what I felt when I was employed by the Generali. Immediate contact with the workaday world deprives me—though inwardly I am as detached as I can be—of the possibility of taking a broad view of matters, just as if I were at the bottom of a ravine, with my head bowed down in addition. 326

The difficulties (which other people sure find incredible) I have in speaking to people arise from the fact that my thinking, or rather the content of my consciousness, is entirely nebulous, that I remain undisturbed by this, so far as it concerns only myself, and am even occasionally self-satisfied; yet conversation with people demands pointedness, solidity, and sustained coherence, qualities not to be found in me. No one will want to lie in clouds of mist with me, and even if someone did, I couldn’t expel the mist from my head; when two people come together it dissolves of itself and is nothing. 329

How time flies; another ten days and I have achieved nothing. It doesn’t come off. A page now and then is successful, but I can’t keep it up, the next day I am powerless. 332

Incapable of living with people, of speaking. Complete immersion in myself, thinking of myself. Apathetic, witless, fearful. I have nothing to say to anyone—never. 334

In a better state because I read Strindberg (Separated). I don’t read him to read him, but rather to lie on his breast. He holds me on his left arm like a child. I sit there like a man on a statue. Ten times I almost slip off, but at the eleventh attempt I sit there firmly, feel secure, and have a wide view…. Chotek Park in the afternoon, read Strindberg, who sustains me. 339

You have the chance, as far as it is at all possible, to make a new beginning. Don’t throw it away. If you insist on digging deep into yourself, you won’t be able to avoid the muck that will well up. But don’t wallow in it. If the infection in your lungs is only a symbol, as you say, a symbol of the infection whose inflammation is called F. and whose depth is its deep justification; if this is so then the medical advice (light, air, sun, rest) is also a symbol. Lay hold of this symbol. 383

In peacetime you don’t get anywhere, in wartime you bleed to death. 384

I can still have passing satisfaction from works like A Country Doctor, provided I can still write such things at all (very improbable). But happiness only if I can raise the world into the pure, the true, and the immutable. 386-7

It is no disproof one one’s presentiment of an ultimate liberation if the next day one’s imprisonment continues on unchanged, or is even made straighter, or if it is even expressly stated that it will never end. All this can rather be the necessary preliminary to an ultimate liberation. 391

Among the young women in the park. No envy. Enough imagination to share their happiness, enough judgment to know I am too weak to have such happiness, foolish enough to think I see to the bottom of my own and their situation. Not foolish enough; there is a tiny crack there, and wind whistles through it and spoils the full effect. 392

There may be a purpose lurking behind the fact that I never learned anything useful and—the two are connected—have allowed myself to become a physical wreck. I did not want to be distracted, did not want to be distracted by the pleasures life has to give a useful and healthy man. As if illness and despair were not just as much of a distraction!

There are several ways in which I could complete this thought and so reach a happy conclusion for myself, but I don’t dare, and don’t believe—at least today, and most of the time as well—that a happy solution exists. 392-3

I do not envy particular married couples, I simply envy all married couples together; and even when I do envy one couple only, it is the happiness of married life in general, in all its infinite variety, that I envy—the happiness to be found in any one marriage, even in the likeliest case, would probably plunge me into despair. 393

I don’t believe people exist whose inner plight resembles mine; still, it is possible for me to imagine such people—but that the secret raven forever flaps about their heads as it does about mine, even to imagine that is impossible. 393

Eternal childhood. Life calls again. 393

It is entirely conceivable that life’s splendor forever lies in wait about each one of us in its fullness, but veiled from view, deep down, invisible, far off. It is there, though, not hostile, not reluctant, not deaf. If you summon it by the right word, by its right name, it will come. This is the essence of magic, which does not create but summons. 393

When in 1937 the mythologist Joseph Campbell began dating his future wife, the dancer Jean Erdman, he gave her a copy of Oswald Spengler’s Decline of the West, an odd courtship gift indeed. While visiting Erdman’s family, they discussed the book. Later:

When in 1937 the mythologist Joseph Campbell began dating his future wife, the dancer Jean Erdman, he gave her a copy of Oswald Spengler’s Decline of the West, an odd courtship gift indeed. While visiting Erdman’s family, they discussed the book. Later:

Here is one the my favorite moments from a writer’s life, followed by one of the saddest. Only seven months apart, they typify the pendulum of great highs and awful lows in

Here is one the my favorite moments from a writer’s life, followed by one of the saddest. Only seven months apart, they typify the pendulum of great highs and awful lows in  [September, 1931, in Tepotzlán, Mexico] They’d arrived, it turned out, on the eve of the Feast of Tepoztecatl, the ancient Aztec god of pulque, corn liquor. Crane had noticed the impressive ruins of the god’s temple, destroyed centuries earlier by the Spanish, set high on the cliff overlooking one end of the valley. The following day, he and Rourke went out in the cornfields, looking for signs of the older Indian civilization that had flourished here before the coming of the Spanish. Together, they found several fragments of Aztec idols that had been turned over by plows. When they showed these to the elders, they were told some of the legends surrounding Tepoztecatl, even as they were served hot coffee laced with pulque. What wonderful people these Indians were, Crane mused, who “still stuck to their ancient rites despite all the oppression of the Spaniards for near 400 years.” In writing The Bridge, except for the New York City cabdriver named Maquokeeta he’d talked with one night, he had had to imagine the Indian through an ersatz American myth and history, and the poem had suffered accordingly. Now he was coming into direct contact with the descendants of the Aztecs. The descent into the essential soil of Mexico had begun in earnest.

[September, 1931, in Tepotzlán, Mexico] They’d arrived, it turned out, on the eve of the Feast of Tepoztecatl, the ancient Aztec god of pulque, corn liquor. Crane had noticed the impressive ruins of the god’s temple, destroyed centuries earlier by the Spanish, set high on the cliff overlooking one end of the valley. The following day, he and Rourke went out in the cornfields, looking for signs of the older Indian civilization that had flourished here before the coming of the Spanish. Together, they found several fragments of Aztec idols that had been turned over by plows. When they showed these to the elders, they were told some of the legends surrounding Tepoztecatl, even as they were served hot coffee laced with pulque. What wonderful people these Indians were, Crane mused, who “still stuck to their ancient rites despite all the oppression of the Spaniards for near 400 years.” In writing The Bridge, except for the New York City cabdriver named Maquokeeta he’d talked with one night, he had had to imagine the Indian through an ersatz American myth and history, and the poem had suffered accordingly. Now he was coming into direct contact with the descendants of the Aztecs. The descent into the essential soil of Mexico had begun in earnest. [April 27, 1932, on the ship Orizaba, ten miles each of the Florida coast, 275 miles north of Havana] ….A few minutes before noon, there was a knock at her door. It was Crane, still in pajamas, but wearing a light topcoat over them. She told him to shave and get dressed and join her for lunch. “I’m not going to make it, dear,” he told her, his voice already drifting. “I’m utterly disgraced.” Nonsense, she told him. How much better he’d feel once he was dressed. “All right, dear,” he said. He leaned over, kissed her goodbye, and closed the door behind him. Then he walked along the promenade deck toward the stern of the ship.

[April 27, 1932, on the ship Orizaba, ten miles each of the Florida coast, 275 miles north of Havana] ….A few minutes before noon, there was a knock at her door. It was Crane, still in pajamas, but wearing a light topcoat over them. She told him to shave and get dressed and join her for lunch. “I’m not going to make it, dear,” he told her, his voice already drifting. “I’m utterly disgraced.” Nonsense, she told him. How much better he’d feel once he was dressed. “All right, dear,” he said. He leaned over, kissed her goodbye, and closed the door behind him. Then he walked along the promenade deck toward the stern of the ship.

In early January, 1924, the poet

In early January, 1924, the poet  Here is a favorite bit from a youthful

Here is a favorite bit from a youthful  Bone Antler Stone by Tim Miller: High Window Press, 80pp ISBN 9780244009595

Bone Antler Stone by Tim Miller: High Window Press, 80pp ISBN 9780244009595

My

My  BOGLAND

BOGLAND

Scone of peat, composite bog-dough

Scone of peat, composite bog-dough

Here are some bits on writing, nature, and anonymous everyday life from

Here are some bits on writing, nature, and anonymous everyday life from