One of the longer myths I’ll post here, the following story is well worth it, and is indeed a master-class in mythology and folklore. Containing shape-changes, chase scenes, mysterious births, borrowed identities, and competitions of all kinds, it is in the best sense a holy mess, including its sudden and (to us) perhaps unsatisfying ending. The story also bears all the hallmarks of being a combination of many tales and poems, including a later overlay of Christian commentary and detail. It is also a wonderful example of how strange the greatest myths are, and how titanic being in the presence of great poetry (and great poets) can be. Enjoy.

The Tale of Gwion Bach

In the days when Arthur began to rule, there was a nobleman living in the land now called Penllyn. His name was Tegid Foel, and his patrimony – according to the story – was the body of water that is known today as Llyn Tegid.

And the story says that he had a wife, and that she was named Ceridwen. She was a magician, says the text, and learned in the three arts: magic, enchantment, and divination. The text also says that Tegid and Ceridwen had a son whose looks, shape and carriage were extraordinarily odious. They named him Morfran, “Great-crow,” but in the end they called him Afagddu, “Utter darkness,” on account of his gloomy appearance. Because of his wretched looks his mother grew very sad in her heart, for she saw clearly that there was neither manner nor means for her son to win acceptance amongst the nobility unless he possessed qualities different from his looks. And so to encompass this matter, she turned her thoughts to contemplation of her arts to see how best she could make him full of the spirit of prophecy and a great prognosticator of the world to come.

After laboring long in her arts, she discovered that there was a way of achieving such knowledge by the special properties of the earth’s herbs and by human effort and cunning. This was the method: choose and gather certain kinds of the earth’s herbs on certain days and hours, put them all in a cauldron of water, and set the cauldron on the fire. It had to be kindled continually in order to boil the cauldron day and night for a year and a day. In that time, she would see ultimately that three drops containing all the virtues of the multitude of herbs would spring forth; on whatever man those three drops fell, she would see that he would be extraordinarily learned in various arts and full of the spirit of prophecy. Furthermore, she would see that all the juice of those herbs except the three aforementioned drops would be as powerful a poison as there could be in the world, and that it would shatter the cauldron and spill the poison across the land.

(Indeed, this tale is illogical and contrary to faith and piety; but as before:) the text of the story shows clearly that she collected great numbers of the earth’s herbs, that she put them into a cauldron of water, and put it on the fire. The story says that she engaged an old blind man to stir the cauldron and tend it, but it says nothing of his name any more than it says who the author of this tale was. However, it does name the lad who was leading this man: Gwion Bach, whom Ceridwen set to stoke the fire under the cauldron. In this way, each kept to his own job, kindling the fire, tending the cauldron, and stirring it, with Ceridwen keeping it full of water and herbs till the end of a year and a day. At that time Ceridwen took hold of Morfran, her son, and stationed him close to the cauldron to receive the drops when their hour to spring forth from the pot arrived. Then Ceridwen set her haunches down to rest.

She was asleep at the moment the three marvellous drops sprung from the cauldron, and they fell upon Gwion Bach, who had shoved Morfran out of the way. Thereupon the cauldron uttered a cry and, from the strength of the poison, shattered. Then Ceridwen woke from her sleep, like one crazed, and saw Gwion. He was filled with wisdom, and could perceive that her mood was so poisonous that she would utterly destroy him as soon as she discovered how he had deprived her son of the marvellous drops. So he took to his heels and fled. But as soon as Ceridwen recovered from her madness, she examined her son, who told her the full account of how Gwion drove him away from where she had stationed him.

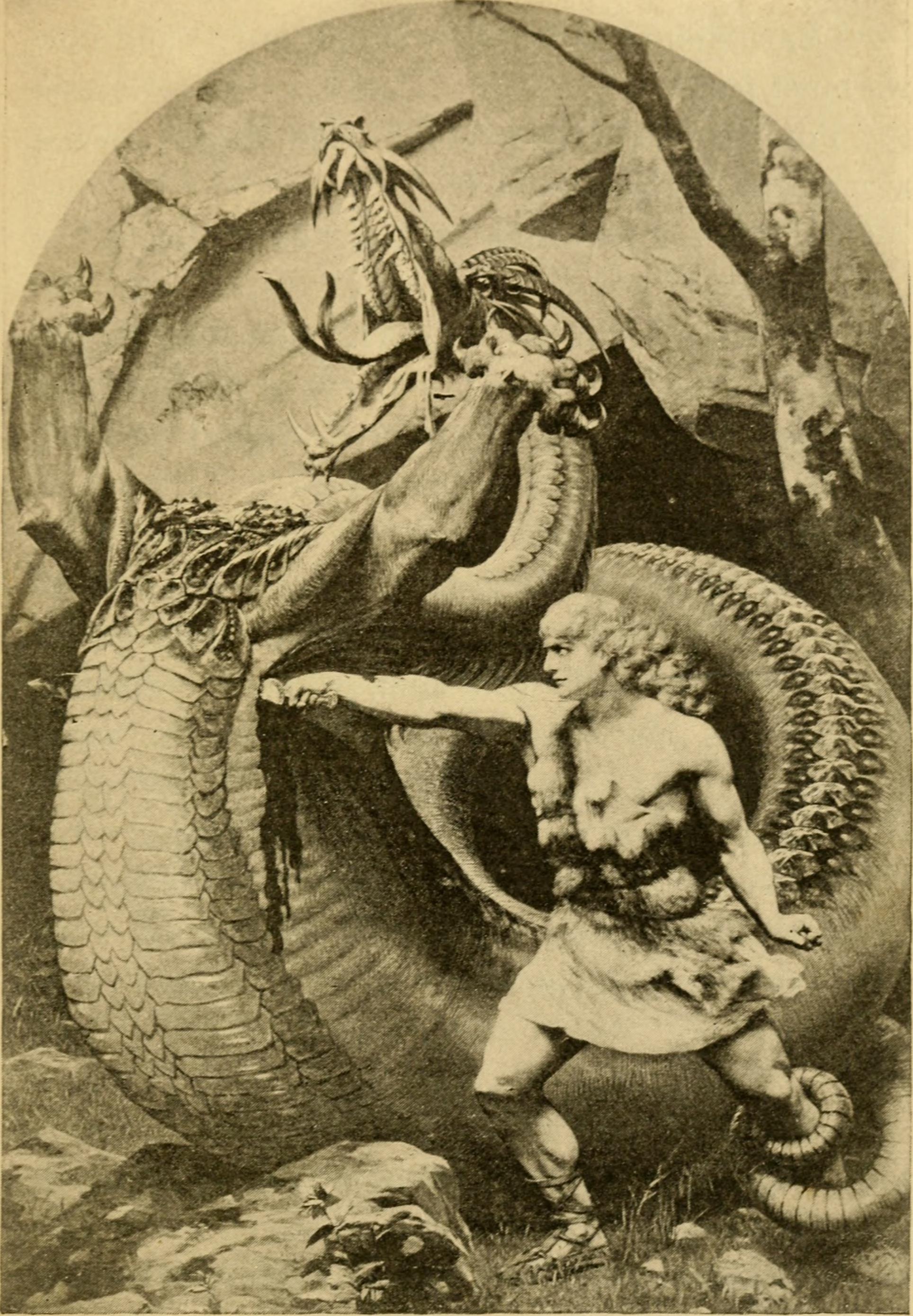

She rushed out of the house in a frenzy in pursuit of Gwion Bach, and the story says that she saw him fleeing swiftly in the form of a hare. She turned herself into a black greyhound and pursued him from one place to another. Finally, after a long pursuit in various shapes, she pressed him so hard that he was forced to flee into a barn where there was a pile of winnowed wheat. There he turned himself into one of the grain; what Ceridwen did then was to change herself into a tufted black hen, and the story says that in this form she swallowed Gwion into her belly.

She carried him there for nine months, at which time she got deliverance of him. But when she gazed upon him after he had come into the world, she could not in her heart do him any physical harm herself, nor could she bear to see anyone else do it. In the end she had the prince put into a coracle or hide-covered basket, which she had fitted snugly all around him; then she caused it to be cast into the lake – according to some books, but some say he was put into a river, others that she had him put into the sea – where he was found a long time afterwards, as the present work will show when the time comes.

The Tale of Taliesin

In the days when Maelgwn Gwynedd was holding court in Castell Deganwy, there was a holy man named Cybi living in Môn. Also in that time there lived a wealthy squire near Caer Deganwy, and the story says he was called Gwyddno Garanhir (he was a lord). The text says that he had a weir on the shore of the Conway adjacent to the sea, in which was caught as much as ten pounds worth of salmon every even of All Hallows. The tale also says that Gwyddno had a son called Elphin son of Gwyddno, who was in service in the court of King Maelgwyn. The text says that he was a noble and generous man, much loved among his companions, but that he was an incorrigible spendthrift – as are the majority of courtiers. As long as Gwyddno’s wealth lasted, Elphin did not lack for money to spend among his friends. By as Gwyddno’s riches began to dwindle, he stopped lavishing money on his son. The latter regretfully informed his friends that he was no longer able to maintain a social life and keep company with them in the manner he had been accustomed to in the past, because his father had fallen on hard times. But as before, he asked some of the men of the court to request fish from the weir as a gift to him on the next All Hallow’s eve; they did that and Gwyddno granted their petition.

And so when the day and the time arrived, Elphin took some servants with him, and came to set up and watch the weir, which he tended from the high tide until the ebb.

When Elphin and his people came within the arms of the weir, they saw there neither head nor tail of a single young salmon; its sides were usually full of such on that night. But the story says that on this occasion he saw nothing but some dark hulk within the enclosure. On account of that, he lowered his head and began to protest his ill-fortune, saying as he turned homeward that his misery and misfortune were greater than those of any man in the world. Then it occurred to him to turn around and see what the thing in the weir was. Immediately, he found a coracle or hide-covered basket, wrapped from above as well as from below. Without delay, he took his knife and cut a slit in the hide, revealing a human forehead.

As soon as Elphin saw the forehead, he said, “behold, the radiant forehead (i. e., tal iesin)!” To those words the child replied from the coracle, “Tal-iesin he is!” People suppose that this was the spirit of Gwion Bach, who had been in the womb of Ceridwen; after she was delivered of him, she had cast him into fresh water or into the sea, as the present work shows above. He had been in the pouch, floating about in the sea, from the beginning of Arthur’s time until about the beginning of Maelgwn’s time – and that was approximately forty years.

Indeed, this is far from reason and sense. But as before, I will keep to the story, which says that Elphin took the bundle and placed it in a basket upon one of the horses. Thereupon, Taliesin sang the stanzas known as Dehuddiant Elphin, “Elphin’s Consolation,” saying as follows:

Fair Elphin, cease your weeping!

Despair brings no profit.

No catch in Gwyddno’s weir

Was ever as good as tonight’s.

Let no one revile what is his.

Man sees not what nurtures him;

Gwyddno’s prayers shall not be in vain.

God breaks not his promises.

Fair Elphin, dry your cheeks!

It does not become you to be sad.

Though you think you got not gain

Undue grief will bring you nothing –

Nor will doubting the miracles of the Lord.

Though I am small, I am gifted.

From the sea and the mountain, from rivers’ depths

God sends bounty to the blessed.

Elphin of the cheerful disposition –

Meek is your mind –

You must not lament so heavily.

Better God than gloomy foreboding.

Though I am frail and little

And wet with the spume of Dylan’s sea,

I shall earn in a day of contention

Riches better than three score for you.

Elphin of the remarkable qualities.

Grieve not for your catch.

Though I am frail here in my bunting,

There are wonders on my tongue.

You must not fear greatly

While I am watching over you.

By remembering the name of the Trinity

None can overcome you.

Together with various other stanzas which he sang to cheer Elphin along the path from there toward home, where Elphin turned over his catch to his wife. She raised him lovingly and dearly.

From that moment on, Elphin’s wealth increased more and more each succeeding day, as well as his favor and acceptance with the king. Some while after this, at the feast of Christmas, the king was holding open court at Deganwy Castle, and all his lords – both spiritual and temporal – were there, with a multitude of knights and squires. Their conversation grew, as they queried one another, saying:

“Is there in the entire world a man as powerful as Maelgwn? Or one to whom the heavenly father has given as many spiritual gifts as God has given him: beauty, shape, nobility, and strength, besides all the powers of the soul?” And with these gifts, they proclaimed that the Father had given him an excellent gift, one that surpassed all of the others, namely, the beauty, appearance, demeanor, wisdom, and faithfulness of his queen. In these virtues, she excelled all the ladies and daughters of the nobility in the entire land. Beside that, they asked themselves: “whose men are more valiant? Whose horses and hounds are swifter and fairer? Whose bards more proficient and wiser than Maelgwn’s?”

At that time poets were received with great esteem among the eminent ones of the realm. And in those days, none of whom we now call “heralds” were appointed to that office, unless they were learned men, and not only in the proper service of kinds and princes, but steeped and skilled in pedigrees, arms, the deeds of kings and princes of foreign kingdoms as well as the ancestors of this kingdom, especially in the history of the chief nobility. Furthermore, each of these bards had to have their responses readily prepared in various languages, such as Latin, French, Welsh, and English, and in addition, be a great historian and good chronicler, be skilled in the composition of poetry and ready to compose metrical stanzas in each of these languages. On this feast, there was in the court of Maelgwn no less than twenty-four of these; chief among them was the one called Heinin Fardd the Poet.

And so after everyone had spoken in praise of the king and his blessings, Elphin happened to say this: “Indeed, no one can compete with a king except another king; but, truly, were he not a king, I would surely say that I had a wife as chaste as any lady in the kingdom. Furthermore, I have a bard who is more proficient than all the king’s bards.”

Some time later, the king’s companions told him the extent of Elphin’s boast, and the king commanded that he be put into a secure prison until he could get confirmation of his wife’s chastity and his poet’s knowledge. And after putting Elphin in one of the castle towers with a heavy chain on his feet (some people say it was a silver chain that was put upon him, because hew as of the king’s blood), the story says that the king sent his son Rhun to test the continence of Elphin’s wife. It says that Rhun was one of the lustiest men in the world, and that neither woman nor maiden with whom he had spent a diverting moment came away with her reputation intact.

As Rhun was hastening toward Elphin’s residence, fully intending to despoil Elphin’s wife, Taliesin was explaining to her how the king had thrown his master into prison and how Rhun was hurrying there with the intention of corrupting her virtue. Because of that he had his mistress dress one of the scullery maids in her own garb. The lady did this cheerfully and unstintingly, adorning the maid’s fingers with the finest rings that she and her husband possessed. In this guise, Taliesin had his mistress seat the girl in her own chamber to sup at her own table and in her own place; Taliesin had made the girl look like his mistress, his mistress like the girl.

As they sat most handsomely at their supper in the manner described above, Rhun appeared suddenly at the court of Elphin. He was received cheerfully, for all the servants knew him well. They escorted him without delay to their mistress’s chamber. The girl disguised as the mistress rose from her supper and greeted him pleasantly, then sat back down to her meal, and Rhun with her. He began to beguile the girl with seductive talk, while she preserved the mien of her mistress.

The story says that the maiden got so inebriated that she fell asleep. It says that Rhun had put a powder in her drink that made her sleep so heavily – if the tale can be believed – that she didn’t even feel him cutting off her little finger, around which was Elphin’s signet ring that he had sent to his wife as a token a short time before. In this way he did his will with the maiden, and afterwards, he took the finger – with the ring on it – to the king as proof. He told him that he had violated her chastity, explaining how he had cut off her finger as he left, without her awakening.

The king took great delight in this news, and, because of it, summoned his council, to whom he explained the whole affair from one end to the other. Then he had Elphin brought from the prison to taunt him for his boast, and said to him as follows:

“It should be clear to you, Elphin, and beyond doubt, that it is nothing but foolishness for any man in the world to trust his wife in the matter of chastity any farther than he can see her. And so that you may harbor no doubts that your wife broke her marriage vows last night, here is her finger as evidence for you, with your own signet ring on it; the one who lay with her cut it off her hand while she slept. So that there is no way that you can argue that she did not violate her fidelity.”

To this Elphin replied, “With your permission, honorable king, indeed, there is no way I can deny my ring, for a number of people know it. But, indeed, I do deny vehemently that the finger encircled by my ring was ever on my wife’s hand, for one sees there three peculiar things not one of which ever characterized a single finger of my wife’s hands. The first of these is that – with your grace’s permission – wherever my wife is at this moment, whether she is sitting, standing, or lying down, this ring will not even fit her thumb! And you can easily see that if was difficult to force the ring over the knuckle of the little finger of the hand from which it was cut. The second thing is that my wife has never gone a single Saturday since I have known here without paring her nails before going to bed. And you can see clearly that the nail of this finger has not been cut for a month. And the third thing, indeed, is that the hand from which this finger was cut kneaded rye dough within the past three days, and I assure you, your graciousness, that my wife has not kneaded rye dough since she became my wife.”

The story says that the king became more outraged at Elphin for standing so firmly against him in the matter of his wife’s fidelity. As a result, the king ordered him to be imprisoned again, saying that he would not gain release from there until he proved true his boast about the wisdom of his bard as well as about the fidelity of his wife.

Those two, meanwhile, were in Elphin’s palace, taking their ease. Then Taliesin related to his mistress how Elphin was in prison on account of them. But he exhorted her to be of good cheer, explaining to her how he would go to the court of Maelgwn to free his master. She asked him how he could set his master free, and he replied as follows:

I shall set out on foot,

Come to the gate,

And make for the hall.

I shall sing my song

And proclaim my verse,

And the lord’s bards I shall inhibit:

Before the chief one

I shall make demands,

And I shall overcome them.

And when the contention comes

In the presence of the chieftains,

And a summons of the minstrels

For precise and harmonious songs

In the court of the scions of nobles,

Companion to Gwion,

There are some who assumed the appearance

Of anguish and great pains.

They shall fall silent by rough words,

If it ever grows ever worse, like Arthur, Chief of givers,

With his blades long and red

From the blood of nobles;

The king’s battle against his enemies,

Whose gentles’ blood flows

From the battle of the woods in the distant North.

May there be neither blessing nor beauty

On Maelgwn Gwynedd,

But let the wrong be avenged –

And the violence and arrogance – finally,

For the act of Rhun his offspring:

Let his lands be desolate,

Let his life be short,

Let the punishment last long

on Maelgwn Gwynedd.

And after that he took leave of his mistress, and came at last to the court of Maelgwn Gwynedd. The latter, in his royal dignity, was going to sit in his hall at supper, as kings and princes were accustomed to do on every high feast in those days.

And as soon as Taliesin came into the hall, he saw a place for himself to sit in an inconspicuous corner, beside the place where the poets and minstrels had to pass to pay their respects and duty to the king – as is still customary in proclaiming largesse in the courts on high holidays, except that they are proclaimed now in French. And so the time came for the bards or the heralds to come and proclaim the largesse, power, and might of the king. They came past the spot where Taliesin sat hunched over in the corner, and as they went by, he puckered his lips and with his finger made a sound like blerum blerum. Those going past paid no attention to him, but continued on until they stood before the king. They performed their customary curtsy as they were obliged to do; not a single word came from their mouths, but they puckered up, made faces at the king, and made the blerum blerum sound on their lips with their fingers as they had seen the lad do it earlier. The sight astonished the king, and he wondered to himself whether they had had too much to drink. So he ordered one of the lords who was administering to his table to go to them and ask them to summon their wits and reflect upon where they were standing and what they were obliged to do. The lord complied.

But they did not stop their nonsense directly, so he sent to them again, and a third time, ordering them to leave the hall; finally, the king asked one of the squires to clout their chief, the one called Heinin Fardd. The squire seized a platter and struck him over the head with it until he fell back on his rump. From that spot, he rose up onto his knees whence he begged the king’s mercy and leave to show him that it was neither of the two failings on them – neither lack of intelligence nor drunkenness – but due to some spirit that was inside the hall. And then Heinin said as follows: “O glorious king! Let it be known to your grace, that it is not from the pickling effect of a surfeit of spirits that we stand here dumb, unable to speak properly, like drunkards, but because of a spirit, who sits in the corner yonder, in the guise of a little man.”

Whereupon, the king ordered a squire to fetch him. He went to the corner where Taliesin sat, and brought him thence before the king, who asked him what sort of thing he was and whence he came. He answered the king in verse, and spoke as follows:

Offical chief-poet

to Elphin am I,

And my native abode

is the land of the Cherubim.

Then the king asked him what he was called, and he answered him saying this:

Johannes the prophet

called me Merlin,

But now all kings

call me Taliesin.

Then the king asked him where he had been, and thereupon he recited his history to the king, as follows here in this work:

I was with my lord

in the heavens

When Lucifer fell

into the depths of hell;

I carried a banner

before Alexander;

I know the stars’ names

from the North to the South

I was in the fort of Gwydion,

in the Tetragramaton;

I was in the canon

when Absalon was killed;

I brought seed down

to the vale of Hebron;

I was in the court of Dôn

before the birth of Gwydion;

I was patriarch

to Elijah and Enoch;

I was head keeper

of the work of Nimrod’s tower;

I was atop the cross

of the merciful son of God;

I was three times

in the prison of Arianrhod;

I was in the ark

with Noah and Alpha;

I witnessed the destruction

of Sodom and Gomorrah;

I was in Africa

before the building of Rome;

I came here

to the survivors of Troy.

And I was with my lord

in the manger of oxen and asses;

I upheld Moses

through the water of Jordan;

I was in the sky

with Mary Magdalen;

I got poetic inspiration

from the cauldron of Ceridwen;

I was poet-harper

to Llon Llychlyn;

I was in Gwynfryn

in the court of Cynfelyn;

In stock and fetters

a day and a year.

I was revealed

in the land of the Trinity;

And I was moved

through the entire universe;

And I shall remain till doomsday,

upon the face of the earth.

And no one knows what my flesh is –

whether meat or fish.

And I was nearly nine months

in the womb of the witch of Ceridwen;

I was formerly Gwion Bach,

but now I am Taliesin.

And the story says that this song amazed the king and his court greatly. Then he sang a song to explain to the king and his people why he had come there and what we was attempting to do, as the following poem sets forth.

Provincial bards! I am contending!

To refrain I am unable.

I shall proclaim in prophetic song

To those that will listen.

And I seek that loss

That I suffer:

Elphin, from the punishment

Of Caer Deganwy.

And from him, my lord will pull

The binding chain.

The Chair of Caer Deganwy –

Mighty is my pride –

Three hundred songs and more

Are the songs I shall sing;

No bard that knows them not

Shall merit spear

Nor stone nor ring,

Nor remain about me.

Elphin son of Gwyddno

Suffers torment now,

’Neath thirtheen locks

For praising his master-bard.

And I am Taliesin,

Chief-poet of the West,

And I shall release Elphin

From the gilded fetters.

After this, as the text shows, he sang a song of succor, and they say that instantly a tempestuous wind arose, until the king and his people felt that the castle would fall upon them. Because of that, the king had Elphin fetched from prison in a hurry, and brought to the side of Taliesin. He is said to have sung a song at that moment that resulted in the opening of the fetters from around his feet – indeed, in my opinion, it is very difficult for anyone to believe that this tale is true. But I will continue the story with as many of the poems by him as I have seen written down.

Following this, he sang the verses called “Interrogation of the Bards,” which follows herewith.

What being first

Made Alpha?

What is the fairest refined language

Designed by the Lord?

What food? What drink?

Whose raiment prudent?

Who endured rejection

From a deceitful land?

Why is a stone hard?

Why is a thorn sharp?

Who is hard as a stone,

And as salty as salt?

Why is the nose like a ridge?

Why is the wheel round?

Why does the tongue articulate

More than any one organ?

Then he sang a series of verses called “The Rebuke of the Bards,” and it begins like this:

If you are a fierce bard

Of spirited inspiration,

Be not testy

In your king’s court,

Unless you know the name for rimin,

And the name for ramin,

And the name for rimiad,

And the name for ramiad,

And the name of your forefather

Before his baptism.

And the name of the firmament,

And the name of the element,

And the name of your language,

And the name of your district.

Company of poets above,

Company of poets below;

My darling is below

’Neath the fetters of Aranrhod.

You certainly do not know

The meaning of what my lips sing,

Nor the true distinction

Between the true and the false.

Bards of limited horizons,

Why do you not flee?

The bard who cannot shut me up

Shall have no quiet

Till he come to rest

Beneath a gravelly grave.

And those who listen to me,

Let God listen to them.

And after this follows the verses called “The Satire on the Bards.”

Minstrels of malfeasance make

Impious lyrics; in their praise

They sing vain and evanescent song,

Ever exercising lies.

They mock guileless men

They corrupt married women,

They despoil Mary’s chaste maidens.

Their lives and times they waste in vain,

They scorn the frail and the guileless,

They drink by night, sleep by day,

Idly, lazily, making their way.

They despise the Church

Lurch toward the taverns;

In harmony with thieves and lechers,

They seek out courts and feasts,

Extol every idiotic utterance,

Praise every deadly sin.

They lead every manner of base life,

Roam every village, town, and land.

The distresses of death concern them not,

Never do they give lodging or alms.

Excessive food they consume.

They rehearse neither psalms nor prayer,

Pay neither tithes nor offerings to God,

Worship not on Holy Days nor the Lord’s day,

Fast on neither Holy Days nor ember days.

Birds fly,

Fish swim,

Bees gather honey,

Vermin crawl;

Everything bustles

To earn its keep

Except minstrels and thieves, the lazy and worthless.

I do not revile your minstrelsy,

For God gave that to ward off evil blasphemy;

But he who practices it in perfidy

Reviles Jesus and his worship.

After Taliesin had freed his master from prison, verified the chastity of his mistress, and silenced the bards so that none of them dared say a single word, he asked Elphin to wager the king that he had a horse faster and swifter than all the king’s horses. Elphin did that.

On that day, time, and place determined – the place known today as Morfa Rhianedd – the king arrived with his people and twenty-four of the swiftest horses he owned. Then, after a long while, the course was set, and a place for the horses to run. Taliesin came there with twenty-four sticks of holly, burnt black. He had the lad who was riding his master’s horse put them under his belt, instructing him to let all the king’s horses go ahead of him, and as he caught up with each of them in turn, to take one of the rods and whip the horse across his rump, and then throw it to the ground. Then take another rod and do in the same manner to each of the horses as he overtook them. And he instructed the rider to observe carefully the spot where his horse finished, and throw down his cap on that spot.

The lad accomplished all of this, both the whipping of each of the king’s horses as well as throwing down his cap in the place where the horse finished. Taliesin brought his master there after his horse won the race, and he and Elphin set me to work to dig a hole. When they had dug the earth to a certain depth, they found a huge cauldron of gold, and therewith Taliesin said, “Elphin, here is payment and reward for you for having brought me from the weir and raising me from that day to this.” In that very place there stands a pool of water, which from that day to this is called “Cauldon’s Pool.”

After that, the king said had Taliesin brought before him, and asked for information concerning the origin of the human race. Forthwith, he sang the verses that follow here below, and that are known today as one of the four pillars of song. They begin as follows:

Here begin the prophecies of Taliesin:

The Lord made

In the midst of Glen Hebron

With his blessed hands,

I know, the shape of Adam.

He made the beautiful;

In the court of paradise,

From a rib, he put together

Fair woman.

Seven hours they

Tended the Orchard

Before Satan’s strife,

Most insistent suitor.

Thence they were driven

Through cold and chill

To lead their lives

In this world.

To bear in affliction

Sons and daughters,

To get tribute

From the land of Asia.

One hundred and eight

Was she fertile,

Bearing a mixed brood,

Masculine and feminine.

And then, openly,

When she bore Abel

And Cain, unconcealable,

Most unredeemable.

To Adam and his mate

Was given a digging shovel

To break the earth

To gain bread.

And shining white wheat

To sow, the instrument

To feed all men

Until the great feast.

Angels sent

From God Almighty

Brought the seed of growth

To Eve.

She hid

A tenth of the gift

So that not all did

The whole garden enclose.

But black rye was had

In place of the fine wheat,

Showing the evil

For stealing.

Because of that treacherous turn,

It is necessary, says Sattwrn,

For each to give his tithe

To God first.

From crimson red wine

Planted on a sunny days,

And the moon’s night prevails

Over white wine.

From wheat of true privilege,

From red wine generous and privileged.

Is made the finely molded body

Of Christ son of Alpha.

From the wafer is the flesh.

From the wine is the flow of blood.

And the words of the Trinity

Consecrated him.

Every sort of mystical book

Of Emmanuel’s work

Rafael brought

To give to Adam.

When he was in ferment,

Above his two jaws

Within the Jordan river

Fasting.

Moses found,

To guard against great need,

The secret of the three

Most famous rods.

Samson got

Within the tower of Babylon

All the magical arts

Of Asia land.

I got, indeed,

In my bardic song,

All the magical arts

Of Europe and Africa.

And I know whence she emanates

And her home and her hospitality,

Her fate and her destiny

Till Doomsday.

Alas, God, how wretched,

Through excessive plaint,

Comes the prophecy

To the race of Troy.

A coiled serpent,

Proud and merciless,

With golden wings

Out of Germany.

It shall conquer

England and Scotland,

From the shore of the Scandinavian Sea

To the Severn.

Then shall the Britons be

Like prisoners,

With status of aliens,

To the Saxons.

Their lord they shall praise.

Their language preserve,

And their land they will lose –

Save wild Wales.

Until comes a certain period

After long servitude,

When shall be of equal duration

The two proud ones.

Then will the Britons gain

Their land and their crown,

And the foreigners

Will disappear.

And the words of the angels

On peace and war

Will be true

Concerning Britain.

And after this he proclaimed to the king various prophecies in verse, concerning the world that would come hereafter.

– “The Tale of Gwion Bach” and “The Tale of Taliesin,” translated by Patrick Ford in The Mabinogi and Other Medieval Welsh Tales, 162-181

Read the other Great Myths Here

Read the other Great Myths Here A brother of the monastery is found to possess God’s gift of poetry [A. D. 680]

A brother of the monastery is found to possess God’s gift of poetry [A. D. 680]

The sad early life of Parzival is narrated here. His father having died while out on crusade, his mother, Herzeloyde, tries to keep all knowledge of knighthood from her Parzival’s awareness. She retreats to the woods with a small retinue, and of course all of her attempts are in vain.

The sad early life of Parzival is narrated here. His father having died while out on crusade, his mother, Herzeloyde, tries to keep all knowledge of knighthood from her Parzival’s awareness. She retreats to the woods with a small retinue, and of course all of her attempts are in vain.

As usual with such stories, childhood is synonymous with the dangers of being children:

As usual with such stories, childhood is synonymous with the dangers of being children: When Culand the smith offered Conchubur his hospitality, he said that a large host should not come, for the feast would be the fruit not of lands and possessions but of his tongs and his two hands. Conchubur went with fifty of his oldest and most illustrious heroes in their chariots. First, however, he visited the playing field, for it was his custom when leaving or returning to seek the boys’ blessing; and he saw Cú Chulaind driving the ball past the three fifties of boys and defeating them. When they drove at the hole, Cú Chulaind filed the hole with his balls, and the boys could not stop them; when the boys drove at the hole, he defended it alone, and not a single ball went in. When they wrestled, he overthrew the three fifties of boys by himself, but all of them together could not overthrow him. When they played at mutual stripping, he stripped them all so that they were stark naked, while they could not take so much as the brooch from his mantle.

When Culand the smith offered Conchubur his hospitality, he said that a large host should not come, for the feast would be the fruit not of lands and possessions but of his tongs and his two hands. Conchubur went with fifty of his oldest and most illustrious heroes in their chariots. First, however, he visited the playing field, for it was his custom when leaving or returning to seek the boys’ blessing; and he saw Cú Chulaind driving the ball past the three fifties of boys and defeating them. When they drove at the hole, Cú Chulaind filed the hole with his balls, and the boys could not stop them; when the boys drove at the hole, he defended it alone, and not a single ball went in. When they wrestled, he overthrew the three fifties of boys by himself, but all of them together could not overthrow him. When they played at mutual stripping, he stripped them all so that they were stark naked, while they could not take so much as the brooch from his mantle. One day when Rāma and the other little sons of the cowherds were playing, they reported to his mother, “Kṛṣṇa has eaten dirt.” Yaśodā took Krishna by the hand and scolded him, for his own good, and she said to him, seeing that his eyes were bewildered with fear, “Naughty boy, why have you secretly eaten dirt?” Kṛṣṇa said, “Mother, I have not eaten. They are all lying. If you think they speak the truth, look at my mouth yourself” “If that is the case, then open your mouth,” she said to the lord Hari [Vishnu], the God of unchallenged sovereignty who had in sport taken the form of a human child, and He opened his mouth.

One day when Rāma and the other little sons of the cowherds were playing, they reported to his mother, “Kṛṣṇa has eaten dirt.” Yaśodā took Krishna by the hand and scolded him, for his own good, and she said to him, seeing that his eyes were bewildered with fear, “Naughty boy, why have you secretly eaten dirt?” Kṛṣṇa said, “Mother, I have not eaten. They are all lying. If you think they speak the truth, look at my mouth yourself” “If that is the case, then open your mouth,” she said to the lord Hari [Vishnu], the God of unchallenged sovereignty who had in sport taken the form of a human child, and He opened his mouth. The story of the Holy Grail’s appearance to a young man named Perceval/Parzival/Parsifal, is told in many places, and goes something like this: he comes by chance upon the Grail Castle, and is introduced to a wounded man, the Fisher King; during a feast that night, the Grail appears, and if only Parzival would ask a human question of his host – “What ails you?” – his wound and his wasted land would be restored. Instead, the propriety of knighthood keeps him from inquiring, and the next morning the castle is empty; upon leaving, it disappears, and he spends many years trying to find it again. The most complete and arguably the best version of this story is that of Wolfram von Eschenbach, who died around 1190; it is given in its entirety here, to see the wealth of detail and asides that go, essentially, into narrating a simple story of youthful tragedy:

The story of the Holy Grail’s appearance to a young man named Perceval/Parzival/Parsifal, is told in many places, and goes something like this: he comes by chance upon the Grail Castle, and is introduced to a wounded man, the Fisher King; during a feast that night, the Grail appears, and if only Parzival would ask a human question of his host – “What ails you?” – his wound and his wasted land would be restored. Instead, the propriety of knighthood keeps him from inquiring, and the next morning the castle is empty; upon leaving, it disappears, and he spends many years trying to find it again. The most complete and arguably the best version of this story is that of Wolfram von Eschenbach, who died around 1190; it is given in its entirety here, to see the wealth of detail and asides that go, essentially, into narrating a simple story of youthful tragedy: The poet/shaman Väinämöinen, in need of new poems and spells in order to build a boat, goes through an ordeal within the belly of a giant, the keeper of those stories. Here, the giant/ogre figure is more primordial and wise and not simply uncivilized and destructive:

The poet/shaman Väinämöinen, in need of new poems and spells in order to build a boat, goes through an ordeal within the belly of a giant, the keeper of those stories. Here, the giant/ogre figure is more primordial and wise and not simply uncivilized and destructive: Odysseus and friends land on the island “of the lawless outrageous Cyclopes,” one-eyed giants who know nothing of planting and harvesting, and who live in caves. They find their way to one of these caves:

Odysseus and friends land on the island “of the lawless outrageous Cyclopes,” one-eyed giants who know nothing of planting and harvesting, and who live in caves. They find their way to one of these caves: rom the Miwok tribe of California, who are now “practically extinct”:

rom the Miwok tribe of California, who are now “practically extinct”: What is the reason for gold being called otter-payment? It is said that when the Aesir went to explore the whole world – Odin and Loki and Haenir – they came to a certain river and went along the river to a certain waterfall, and by the waterfall there was an otter and it had caught a salmon in the waterfall and was eating it with eyes half-closed. Then Loki picked up a stone and threw it at the otter and hit its head. Then Loki was triumphant at his catch, that he had got in one blow otter and salmon.

What is the reason for gold being called otter-payment? It is said that when the Aesir went to explore the whole world – Odin and Loki and Haenir – they came to a certain river and went along the river to a certain waterfall, and by the waterfall there was an otter and it had caught a salmon in the waterfall and was eating it with eyes half-closed. Then Loki picked up a stone and threw it at the otter and hit its head. Then Loki was triumphant at his catch, that he had got in one blow otter and salmon. The Indian legend of the “Face of Glory” begins, like that of the Man-Lion, with the case of an infinitely ambitious king who through extraordinary austerities had gained the power to unseat the gods and was now sole sovereign of the universe. His name was Jalandhara, “Water Carrier,” and he conceived the impudent notion of challenging even Shiva, the supreme sustainer of the world. (In the Man-Lion legend this was the role of Vishnu. The present legend belongs to the mythology of Shiva.) The king’s idea was to demand that Shiva should surrender to him the goddess Parvati, his wife, and to this end he sent as messenger a terrible monster called Rahu, “the Seizer,” whose usual role is to seize and eclipse the moon.

The Indian legend of the “Face of Glory” begins, like that of the Man-Lion, with the case of an infinitely ambitious king who through extraordinary austerities had gained the power to unseat the gods and was now sole sovereign of the universe. His name was Jalandhara, “Water Carrier,” and he conceived the impudent notion of challenging even Shiva, the supreme sustainer of the world. (In the Man-Lion legend this was the role of Vishnu. The present legend belongs to the mythology of Shiva.) The king’s idea was to demand that Shiva should surrender to him the goddess Parvati, his wife, and to this end he sent as messenger a terrible monster called Rahu, “the Seizer,” whose usual role is to seize and eclipse the moon. In one of the great gymnastic feats of world literature, Dante and Virgil climb the body of Satan, located as it is in the center of the earth. Travelling upside down and changing hemispheres as they go, they emerge to see the Mountain of Purgatory, which was created by the crash of Lucifer’s body as it fell from heaven:

In one of the great gymnastic feats of world literature, Dante and Virgil climb the body of Satan, located as it is in the center of the earth. Travelling upside down and changing hemispheres as they go, they emerge to see the Mountain of Purgatory, which was created by the crash of Lucifer’s body as it fell from heaven: