Ted Hughes: 14 Poems from "Crow" (new episode) – Human Voices Wake Us

Entries in the Anthology series organize my favorite anecdotes about artists, writers, and historical events, and are always being updated. While I love and depend on the exhaustive biography or study, in many ways the disconnected stories and fragments have been more important in my day-to-day living with art, literature and history. As such, nothing original is assumed here, and nearly everything in these pieces is built either on quotations from the historical personages themselves, or from the scholars who have written about them.

[1] Born in 1882, the American painter Edward Hopper (1882 – 1967) made only three trips to the Europe, and these only over a three-year period, between 1907 and 1910. This compared to the duty many artists felt to not only go to Paris, but to live there.

He later remarked that, “In my day you had to go to Paris. Now you can go to Hoboken, it’s just as good.”

[2] Zeuxis was an artist in ancient Greece, but little of his work survives other than colorful anecdotes. In one, he apparently painted grapes so convincingly birds tried to pick at them.

For his part, Hopper painted bedbugs on a fellow art-student’s pillow.

[3] Ivo Kranzfelder remarks that, “By the early 1920s Hopper had already found the style he was to employ with little alteration until the 1960s.” Like Vermeer in the mid-1600s, there is a sense from Hopper of a man painting the same room, the same landscape, the same people, over and over, and finding a new word to describe them each time. By the end of his life he had created a family of secluded people whose solitude was set in the isolated city and country. The paintings all seem pieces of one large work, perhaps called The Whole of Hopper.

In the same way, we can see his nudes “grow old with him” during the same period, since after his marriage his only model was his wife, Josephine.

[4] Hopper said little about his own work, let alone that of others. One critic mentions the dearth of artists “who let the opportunity for self-commentary pass,” but Hopper was one of them. Yet he was not entirely devoid of calculation, since he is also supposed to have remarked, ridiculously, “The only real influence I’ve ever had was myself.”

Still, his silence was real enough, which added to his simple images being hard to interpret—which is usually code for “easy to over-interpret.” In other words, hard for critics to write about, but easy enough for the non-critic to simply experience.

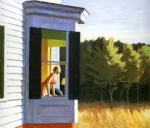

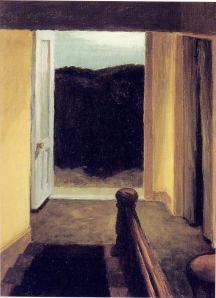

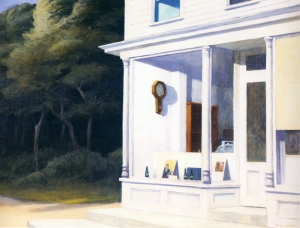

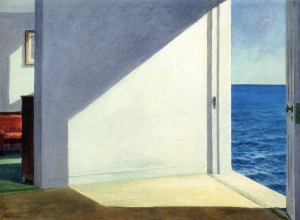

[5] Only rarely does his calm and detached realism seem alarming: Stairway gazes down from the middle of a staircase and an opened front door that looks out onto dark mass beneath a blue sky—or the suggestion that the darkness is getting closer; Seven a.m. shows a shop-window and building butting up against a forest that makes both feel out of place; South Carolina Morning has a piece of sidewalk and the suggestion of a large building (and an impatient woman in the doorway, wondering what the viewer is doing there) set down in the middle of what looks like a wheatfield extending to the horizon; similarly, People in the Sun shows the same slab of pavement and the same wheatfield, this time limited by a run of small hills, all while a curious group of people lounge in chairs and stare off beyond the painting; and perhaps most jarring of all, like something out of Magritte, is Room by the Sea, a living room and a front door which opens onto the ocean, as if an entire house had been cast away on the water.

[6] Early in his career, Hopper painted Soir Blue, in which the artist, seated outside amid the variety of French society (a pimp, prostitute, soldier, and married couple) is depicted amid them as a clown. In his last work, Two Comedians, both he and his wife (also a painter) are shown, if not as clowns then perhaps as mimes, alone on an imaginary stage and taking their leave.

There is so much here: art as serious, but not taken seriously; the artist as the revealer of society to itself, but rarely recognized as such, and in any event mostly seen as masked or made up, never inconspicuous, never fitting in the way the watching audience (or the self-absorbed lovers, whores, or military men) casually belong to everyday life.

But there’s also the jester (think of Shakespeare’s fools) who is actually wise, or the trickster from mythology, or even the magician.

[7] “I was never able to paint what I set out to paint,” Hopper said. Later he added that his ideal work was to be done “with such simple honesty and effacement of the mechanics of art as to give almost the shock of reality itself.”

Hopper might be surprised, or actually he must have known, that some of his pictures give just this shock. This is especially so in those paintings whose focus is a man or woman whose gaze (out a window or down a street) is on something we cannot see; or those paintings of trains (Railroad Train) or small-town streets (Early Sunday Morning) whose beginning or end extend beyond the frame.

There is an endlessness about these gazes and these scenes, and this is the shock of reality. The paintings remind us to look, to never stop looking–but also to admit that they cannot contain the whole world. To use the familiar illustration, there is the humility that the painting is the finger pointing at the moon, rather than the moon itself; there is the humility that art or the artist or the schools of art do not matter, so much as meaning being pointed to.

[8] Kranzfelder remarks that Hopper’s scenes of apparent desolation and loneliness—of something like Gas, a painting split between a forest and a filling station, or his famous Nighthawks, depicting a group of people at an all-night diner flooded with unnatural light—nevertheless “evokes no idyllic pre-industrial state, nor does it celebrate mechanization.”

For there have certainly always been lone or lonely individuals in buildings, as in his House at Dusk or Room in New York or Night Windows, or the solitary woman eating out in Automat; and since the invention of architecture, there have certainly always been the jarring juxtaposition of the places we live with the outside world, as in Cape Cod Morning; and people crowding around a building in the fog have probably always looked something like New York Corner (Corner Saloon); and Hopper’s paintings of theaters certainly have their corollaries in public meeting places from Mesopotamia to today: the lonely person standing off to the side, ignoring the performance (New York Movie), or the strange loneliness of being part of an the audience that should yield intimacy (Intermission, and Solitary Figure in a Theatre).

In none of these images, or in any of his paintings of people isolated in their homes, on the street, in offices or restaurants or elsewhere–or even his paintings of empty stairwells–does Hopper seem to be commenting on the particular, twentieth-century malaise of not feeling at home at home, or not feeling a part of the world when in the world, and therefore blaming it on urban life, on cars or trains, or technology in general. Rather, he is only illustrating our own peculiar version of these feelings, and he does it like no one else.